ILLUSTRATION FEATURE Art and Storytelling

Stephanie Cotela discusses the impact of art and colour in children's literature.

At the first session of my children’s book club, staring out at a dozen chirpy, wiggling three- to five-year-olds, I was anxious about what I had planned and hoped it was enough to grab and sustain their attention. I began by reading a picture book to the group.

Most of the children sat quietly, but few were excited. I hadn’t captured my audience. I stopped reading, pointed to an illustrated page and asked the children to tell me about it. Some spoke about the characters and what they were doing, others talked about the setting and where the character was going. Now, they were getting excited.

|

| Stephanie Cotela's Book Club Banner |

Next I spread squares of paper, with an image on each, across the floor and instructed the children to choose up to five squares to create their own story. They could put the squares in a line, draw a picture based on the squares, write a story or simply tell their story to the group. They all made pictures incorporating colour, glitter, stickers or embellishments.

The book club went on hiatus during lockdown and the task of home-schooling commenced. I was one of those parents, who gave up after the first week. The only academic activities that remained were drawing and reading.

|

| Draw with Rob, By Rob Biddulph, published by HarperCollins |

Rob Biddulph’s YouTube series, Draw with Rob, was a staple in our household. Even I participated. (My stick-figure-level drawing and my writing improved). My children created characters, gave them names, attributes and eventually, created cohesive stories, with a beginning, middle and end. This was something that my then seven-year-old had struggled with previously. Given the images to put in sequential order, the concept of beginning, middle and end didn’t come naturally to him. But when he drew the images himself, something clicked.

I wondered, why, in primary education, isn’t drawing paramount for early readers? Equally, why is art sidelined as children move through school? Surely, nurturing creativity, alongside academics, is a positive thing. It’s widely acknowledged that children who are exposed to art are more likely to become critical thinkers, ask questions about the world around them and draw connections. Toddlers naturally practise visual discrimination when they sort objects by shape, colour, texture, pattern or size. Their understanding of why certain things belong together is a milestone in cognitive learning. Through colour, they learn to identify their feelings and emotions. This self-awareness is linked to confidence in decision making, engaging with peers and imaginative play.

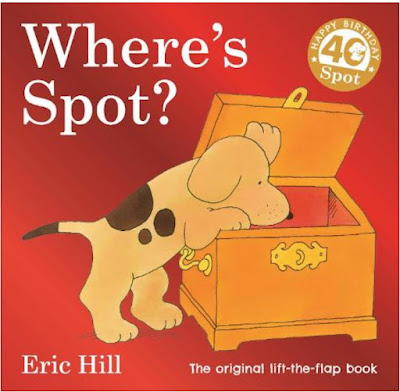

For pre-readers, visual storytelling encourages a wider understanding of characters, plot and setting. The aesthetics need not be complex for a child to bond with a character. For example, Eric Hill’s Spot books, featuring a yellow dog who tackles simple everyday activities, illustrated in bold colours with no more than a few words per page, have sold over 60 million copies worldwide in over sixty languages.

|

| Where's Spot, by Eric Hill, published by Penguin Random House |

In 2014, picture book author/illustrator, Ed Vere, teamed up with Charlotte Hacking from the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) to launch The Power of Pictures project, as a means to 'ensure primary school children have access to the best possible literacy teaching and a passion for picture books.' Their mission is 'to foster children’s love of drawing throughout primary school' by giving teachers the tools and confidence they need, not only to encourage their students to draw, but for them to draw as well. Vere’s philosophy is centred on the notion that drawing makes us think and form ideas before we start writing. Moreover, including drawing in creative writing lessons is inclusive of children who think visually, as is the case with my son. The option to 'draw stories' also benefits reluctant handwriters, who would otherwise dread the task. The Power of Pictures is rooted in the ideology that children who learn through picture books, drawing and creative writing develop the literacy skills to sustain lifelong reading and storytelling.

When my book club resumed, I focused on illustrations instead of words, relying on wordless picture books to demonstrate story structure and encourage the children to 'draw' their own stories.

The following wordless picture books perfectly exemplify the impact of art and colour in children’s literature:

|

| You Can't Take a Balloon Into the Metropolitan Museum, By Jacqueline Preiss Weitzman and Robin Preiss Glasser, published by Penguin Random House |

In this book, a little girl is forced to leave her yellow balloon tied to the handrail outside the Metropolitan Museum while she goes inside with her grandmother. The balloon becomes loose and floats from one New York City landmark to another. A security guard makes chase and is joined by more people each time it floats by them. Meanwhile, the works of art the little girl and her grandmother view inside the museum, mirror the scenes taking place outside the museum. My favourite thing about this book is the 'aha!' moments when children make connections between the art inside and the world outside the museum.

|

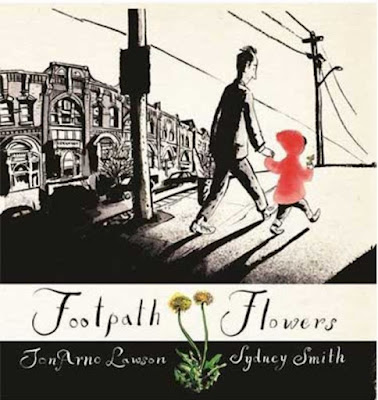

| Footpath Flowers, JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith, published by Walker Books |

In Footpath Flowers a little girl, accompanied by her distracted father, walks through the town collecting wild flowers and giving them to the people and animals she passes along the way. Against the otherwise black and white landscape, she wears a red coat. The flowers, details, people and animals she encounters are also in colour. This is a gentle message about noticing the small things, which children do unconsciously but adults seldom prioritise, and the beauty of generosity. The splashes of colour add a level of emotion that elevates the book’s message.

|

| 10 Minutes to Bedtime, By Peggy Rathmann, published by Penguin Putnam |

Ten Minutes Till Bedtime is a lively, quirky and humorous countdown to bedtime in which a little boy is the main attraction for his pet hamster’s ‘bedtime tour.’ The hamster guides a large group of other hamsters around the house to watch the boy complete his pre-bedtime tasks. He has ten minutes to pull on his pyjamas, brush his teeth and read a bedtime story. It’s a fun read with lots of rich colourful detail, backwards counting and a great opportunity for young readers to familiarise themselves with story structure by recapping the chronology of bedtime tasks.

Header picture: You Can't Take a Balloon into the Metropolitan Museum, By Jacqueline Preiss Weitzman and Robin Preiss Glasser, published by Penguin Random House

******************************************************

Stephanie Cotela is an art historian with experience in the art world on both sides of the pond. She writes PB, MG and YA and has been longlisted in the WriteMentor Children's Novel Award. Find her on Twitter

No comments:

We love comments and really appreciate the time it takes to leave one.

Interesting and pithy reactions to a post are brilliant but we also LOVE it when people just say they've read and enjoyed.

We've made it easy to comment by losing the 'are you human?' test, which means we get a lot of spam. Fortunately, Blogger recognises these, so most, if not all, anonymous comments are deleted without reading.