REPRESENTATION Young Carers

We celebrated Young Carers Action Day on 16 March, which provides us with as an excellent opportunity to acknowledge the experiences of young people who are also carers to their family members or someone in their community. Words & Pictures Editor, Gulfem Wormald, spoke to authors Sylvia Heir and Sally Doherty, whose novels feature protagonists who are young carers.

Which books or projects have you been involved with that represent young carers in children's literature?

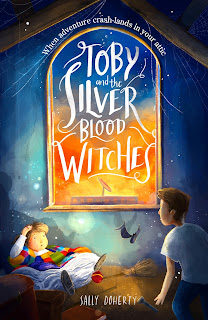

Sally: My debut middle grade book, Toby and the Silver Blood Witches, published in July 2021, features a young carer whose mum is bedbound with ME. Whilst this is a main theme in the book, it’s also important to show that young carers have other aspects to their life. So it’s the backdrop to a magical adventure which helps Toby come to terms with his situation.

Sylvia: My debut novel, Sea Change, is a young adult crime novel set in a small village in the Scottish Highlands. The main character is Alex, a sixteen-year-old schoolboy who is struggling to care for his mum and bring in extra cash following the tragic death of his father in a fishing accident.

What was your biggest motivation to include a young carer in

your work?

Sally: I have lived with severe ME myself for sixteen years and am very aware of the stresses and responsibilities borne by family members who become carers. Much of illness and caring happens behind closed doors, so I wanted to raise awareness of what it’s like, as well as showing young carers that they’re not alone and it’s OK if they’re struggling.

Sylvia: I have been a teacher working with teenagers for over thirty years, including in social services establishments and special needs departments. This gave me the motivation to incorporate, in my fiction, the varied experiences of young people being educated outside the mainstream system, with the express goal of normalising their lived reality. A significant number of these young people were fulfilling a caring role within their families.

My primary goal when I began writing Sea Change was to create a well-written and gripping narrative, with my main character presenting qualities and attributes that I’d frequently witnessed from the young people with whom I had worked.

I felt this ‘inclusion’ was in line with the growing demand for a realistic portrayal of a cast of diverse individuals in YA fiction, a slice of real life as it were, providing the opportunity for all young people to see themselves reflected in what they read, as well as for readers in general to recognise in the text the multiplicity of their wider community.

Sally: Writing about Toby’s life came very naturally to me. However, it’s always a concern when

writing about an underrepresented experience that other people may have different

experiences. You’re never going to be able to represent everyone from that particular

community – you can only write the best you can from your own heart and what you know.

|

| Sylvia Heir |

Have you had any specific challenges about including a young carer in your work?

Sylvia: I am not afraid to share that my own background is from a working-class family and both my parents were mill workers. One of my parents suffered significant injuries while at work, which, of course, affected the family dynamics. However, I do question whether writers who feel compelled to portray a young carer in their work must have personally experienced the circumstances they are revealing. When reflecting on including a young carer in my creative work, various questions troubled me, including: ‘how far can a writer stray from their own lived experience?’ and ‘how can a writer avoid tokenism or cultural appropriation when writing for inclusion?’ From these deliberations, I found that my intention to portray characters away from the mainstream was supported by those calling for greater diversity in YA fiction, as was my intention to keep my inclusion ‘low key’ by not making the marginalised position of the characters the issue of the story. Yet these same intentions were problematic when I considered arguments, for example, regarding tokenism.

I also discovered that I was far from alone in my uncertainties, and that similar reservations are being constantly expressed by other authors, not least in SCBWI presentations and discussions.

Therefore, as part of my research, I wished to understand the opinions and recommendations regarding inclusion being presented by professionals in the publishing industry along with those put forward by campaigning individuals and organisations with a view to gathering data for my creative work.

Did anyone or any specific incident inspire you to write about this theme?

Sylvia: From an early stage in my writing, I knew I would never be able to use somebody else’s unique life story as a base for my creative work. However, I did feel that the qualities and emotions revealed by the young people I have encountered could be features of characters in my fictional worlds. I’ve met youngsters experiencing guilt; shame; loneliness; feelings of inadequacy, anger and resentments, which were sometimes turned inwards; and the need to keep secrets. Yet I also witnessed in these same people resilience, loyalty and determination. There are people in the world living with these issues; they need to be respected but also find representation in literature.

|

| Cover of Toby and the Sliver Blood Witches |

What sort of reaction (positive and negative) did you receive?

Sylvia: I did receive positive feedback from authors who were also wrestling with these topics during the writing of the book. However, I have had little feedback from the published work. Maybe this is because the book is perceived to be genre fiction rather than being issue led? Or maybe my ‘low-key’ has worked and the characters exist as themselves in their own setting?

Do you have any advice for authors/illustrators who want to

include underrepresented groups or sensitive themes in their

work?

Sally: This is a tricky one. A lot of people from underrepresented groups believe that books

containing diverse protagonists and themes should be own voices – that is to say, written

by someone from that community. I think if you want to write an experience you may not

be familiar with, first ask yourself if you can represent it accurately and if it is your place

to do so. If you still want to go ahead, then research, research, research!

Sylvia: The push to encourage a greater diversity of writers into the publishing world to extend the current, narrow picture, is separate to the issue of any writer, whether from a marginalised community or from the mainstream, creating a narrative which includes characters ‘other’ to the mainstream, and which is from a different perspective than the writer’s own background.

While researching for Sea Change, I came to understand that if they so wish, writers can use their work to challenge their own preconceptions by venturing into new territories. Also, through their practice, writers have the option and the opportunity to challenge the current situation of the over-representation of mainstream cultures in YA fiction.

As a conclusion to my research, I came to understand that writing for ‘inclusion’ means being open-minded, risking failure and aiming for success. It means trying to ‘get it right’ through research, collaboration and feedback and writing without labels. It means looking for, and owning, your own deficiencies, prejudices, insecurities, chippiness, blind spots, personal agendas and privileges; and, if you are a member of a marginalised community, it means engaging with your own feelings associated with that sense of being ‘outwith’ with an aim to translate them into your characters. I found that writing for inclusion means recognising and avoiding stereotypes, tokenism, appropriation and exploitation as well as seeing and pushing against inequality and prejudice. It means weaving in the reality of injustices based on difference, such as hardship and despair, with the celebration of marginalised cultures, aiming for a text with a polyphonic texture in the hope that readers will understand, empathise and, where relevant, possibly realise empowerment.

When writing diversity as inclusion for an adolescent readership, it means all this and more. It means being mindful of readership expectations, reading desires and reading habits, and paying attention to responsibilities without being patronising. It means writing with empathy and re-engaging with the adolescent in yourself.

Would you like to add anything else?

Sylvia: The debates are ongoing. It would be great to say movements within the industry, such as the Penguin Random House LIVE mentoring scheme and Curtis Brown Creative’s Breakthrough Writers' Programme, are helping authors from under-represented communities find their place in the book world. Yet looking at the top one hundred bestselling book charts in any online or High Street bookstore would suggest that there is plenty more work to be done.

Sally Doherty lives in leafy Surrey with her husband and three-legged Labrador. A year after graduating from university, she unexpectedly fell ill with ME. Being stuck at home and often in bed, however, has lit a cauldron of stories bubbling inside her imagination. She dabbles in flash fiction with pieces published here and there, including winning Retreat West’s micro fiction competition four times. Sally's debut middle grade novel, Toby and the Silver Blood Witches, was published in July 2021 and is the first in a trilogy. Ten percent of profits go to the ME Association. You can find her on Twitter @Sally_writes.

Writing for inclusion is problematic. Who draws the lines? Who is allowed to even peer over these lines? Authors have enough of a challenge just getting their work seen. Why would they add extra hurdles? However, along with many other authors, I am keen to engage in these discussions. And, following these discussions, I am aware that I need to constantly examine my own position and learn and adapt. And, when I can, be brave.

*Feature image by Tita Berredo

Sally Doherty lives in leafy Surrey with her husband and three-legged Labrador. A year after graduating from university, she unexpectedly fell ill with ME. Being stuck at home and often in bed, however, has lit a cauldron of stories bubbling inside her imagination. She dabbles in flash fiction with pieces published here and there, including winning Retreat West’s micro fiction competition four times. Sally's debut middle grade novel, Toby and the Silver Blood Witches, was published in July 2021 and is the first in a trilogy. Ten percent of profits go to the ME Association. You can find her on Twitter @Sally_writes.

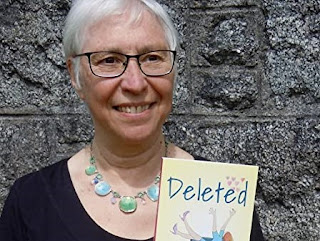

Sylvia Heir gained a Doctor of Fine Art degree in Creative Writing from University of

Glasgow in 2018. She gave a presentation on her DFA research to the National Association

of Writers in Education conference and an article based on her findings is published in their

magazine, Writing in Education.

She received a Scottish Book Trust New Writer Award for children’s fiction.

She has attended Arvon Foundation and Moniack Mhor writing courses with tutors

including Malorie Blackman, Melvin Burgess and Keith Gray.

Sylvia was shortlisted for the Penguin Random House mentorship scheme following

their WriteNow Live initiative for under-represented writers.

She has three novels published for young adults, all set in the Scottish Highlands. Sea

Change was her debut YA crime novel. Deleted and Delivered are the first two YA romance

books in her Love and the Village series. Deleted has also been translated into Scottish Gaelic

as Dubh às. Her radio play, One Last Push, was broadcast by BBC Radio Scotland.

Tita Berredo is Illustration Features Editor for Words & Pictures. She has a Master's degree in Children's Literature and Illustration from Goldsmiths UOL, and a background in social communications, marketing and publicity. www.titaberredo.comwww.titaberredo.com

No comments:

We love comments and really appreciate the time it takes to leave one.

Interesting and pithy reactions to a post are brilliant but we also LOVE it when people just say they've read and enjoyed.

We've made it easy to comment by losing the 'are you human?' test, which means we get a lot of spam. Fortunately, Blogger recognises these, so most, if not all, anonymous comments are deleted without reading.