SPECIAL FEATURE Dyslexia, neurodivergence & wasted talent (part 2)

Award-winning author Matt Killeen continues his examination of what it means to be neurodivergent in a neurotypical world.

I have always been different. I could feel it in my bones. I could kid myself that if I did all the right things I could be like everyone else, but I couldn’t, so I made a virtue of being a bit weird. I got good at it, and better at pretending, but lately I’m feeling that difference all over again. I’m lawful good, and the world is becoming more chaotic evil every day. The stress of this is affecting my ability to do anything.

How many of SCBWI might this describe?

Back in school I assumed I was neurotypical, although I wouldn’t have known the phrase. Autism was defined by narrow criteria that I was nowhere near meeting. I was a high-flyer, with no apparent learning disability, and ADHD wouldn’t appear in the DSM for a few years yet.

But I was struggling, with my ability to retain information waning week by week. Stuff I absolutely had to remember was like water through my fingertips. No amount of lists or planners made any difference. I had mastered my “temper” by the end of primary school, but the same fizzy mental collapse now coalesced round my academic struggle. I was creative with a vivid imagination, but clumsy and chaotic, finding the application necessary for most endeavours almost impossible. Eventually I drew comfort from my status as a “difficult” student, finally finding rock music, where flakiness seemed to be a requirement. In other words, I stopped going in. Things were more interesting in my head.

People don’t want to label their children with diagnoses, but as a tweet I saw recently reminded me, I had plenty of labels back then – lazy, forgetful, stupid, angry, rebellious, a problem.

A fiercely creative rebel is, of course, a marketable commodity. My eventual status as a published author surprised few, writing being possibly the best job for people who have trouble working for others, or who have trouble making themselves understood in the real world. I’d done a lot of work on myself down the years and had got to a very good place. I met a woman who gave me belief that I might just be alright doing what I think is best without any external certification, and I prospered.

Except lately, when I started to find life very difficult indeed. It was both exacerbated and obfuscated by a Lockdown that crystallised the fact that, I am not okay.

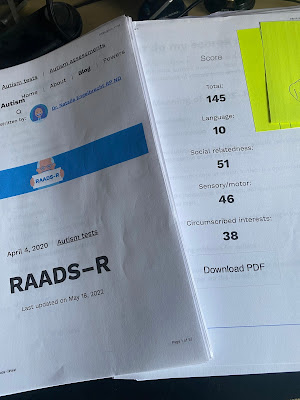

Matt found the Embrace Autism website and took the tests

This year’s SCBWI conference was the first one in a long, long time and we all spent a good while catching up, after some pretty traumatic times. Armed with my new-found knowledge, it was clear to me that a lot of us are neurodivergent, and we’re just cottoning on to it.

What does that mean for us exactly? Certainly, I think most of society’s most interesting artists, writers and creators are autistic. We think differently, or at least, everything that’s interesting and quixotic is the result of our minds at work. It’s why we do what we do. The difficulty of functioning in a world not designed for us, also explains why so many artists can be difficult to work with, or come across as assholes, or self-medicate.

Orphan Monster Spy, which won the Costa Book Awards in 2018, and its sequel Devil Darling Spy

As we age – and hopefully find a little stability among those who genuinely love us – living an inauthentic life is no longer acceptable to us. It does not, in fact, work for us, and we have a lifetime’s worth of examples. As children move on, we have space to come out of crisis mode. We stop masking because we’ve had enough of it. We have no more **** left to give. Behold our fields and see that they are barren.

But, aren’t we all a bit autistic? Well, this question is at once a great way of normalising neurodivergence and a massively disrespectful minimisation of a significant set of challenges. It is an example of two things: one, the need of the able, and neurotypical, to look down on the ill and complex. Two, I believe it indicates that there are many, many more neurodivergent people than anyone previously supposed. The neurotypical mindset that rules the world does not suit a hefty chunk of the population and that world needs to start making accommodations.

And the trauma of the last few years – and it is a trauma – means we can’t go on pretending. We have to deal with it. Yes, this causes its own problems, but this is a journey. It starts with forgiving ourselves for what we can’t control, and then making the world listen to us. We owe it to ourselves, our writing, and each other.

*Find Dyslexia, neurodivergence & wasted talent (part 1) in Words & Pictures, November 2022, here.

*Header image: https://suelarkey.com.au/neurodiversityblog/

*

Matt Killeen has worked as an advertising copywriter, and music and sports journalist. He became a writer for the LEGO® company in 2010 and continues to write for the 2269 project and PC Gamer. He lives near London with his soulmate, children, dog and musical instruments. His first novel Orphan Monster Spy was shortlisted for the Costa Book Awards and the Branford Boase Award, and won the 2019 SCBWI Crystal Kite. The sequel, Devil Darling Spy, was published in spring 2020.

Twitter: @by_Matt_Killeen. Instagram: @by_Matt_Killeen.

*

No comments:

We love comments and really appreciate the time it takes to leave one.

Interesting and pithy reactions to a post are brilliant but we also LOVE it when people just say they've read and enjoyed.

We've made it easy to comment by losing the 'are you human?' test, which means we get a lot of spam. Fortunately, Blogger recognises these, so most, if not all, anonymous comments are deleted without reading.