INSPIRATIONS FROM THE BOOKSHELF Margery Gill

Alison Padley-Woods invites illustrator Martha Lightfoot to tell us about an illustrator who has most inspired her.

When I left primary school, my teacher gave each of us a book - for me he chose Susan Cooper’s Over Sea, Under Stone, illustrated by Margery Gill. I fell in love with it, and went on to devour the whole Dark is Rising series.

To my eleven-year-old eyes, Margery Gill’s illustrations were perfect – they showed me the story, without distracting me by contradicting the author. And the best illustrations let us imagine we’re in the story too. Three siblings on holiday in Cornwall who find themselves on a quest for a missing grail; part of the battle between Dark and Light ... that could have been me and my brothers!

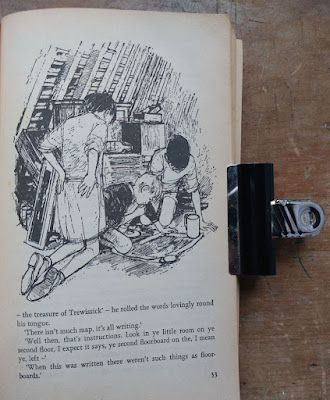

|

| Over Sea, Under Stone, by Susan Cooper, illustrated by Margery Gill, Jonathan Cape, 1965 |

I later came across Gill's work in Apple Bough by Noel Streatfeild, and The Bus Under the Leaves by Margaret Mahy, but it was that first book that really stuck with me.

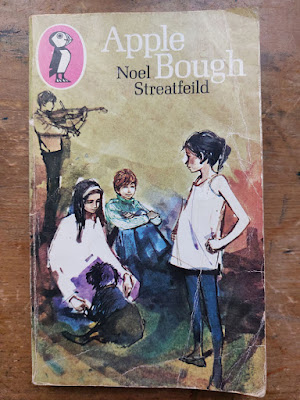

|

| Apple Bough, by Neil Streatfeild, illustrated by Margery Gill, Puffin, 1975 |

Margery Gill (1925 - 2008) was a prolific illustrator of children’s fiction, best known for her pen and ink drawings and beautiful covers in limited palettes.

Her drawings of children are often described as ‘unsentimental’ and the faces aren’t overly expressive, leaving the reader free to interpret the children’s feelings. Characters are sometimes shown from behind, or with the side of the face glimpsed – we’re seeing what they’re seeing, as well as observing them.

Many of the scenes are contemplative – children crouching, or lying on their tummies or backs, often angular, and long-legged. It’s no surprise to hear that she drew from her daughters and the neighbouring children.

Margery was born in Coatbridge, Lanarkshire in 1925, and her family moved to London in the 1930s. She went to Harrow School of Art aged 14, then studied etching and engraving at the Royal College of Art. In 1946 she illustrated her first book, A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson (OUP), and married actor Patrick Jordan. Over the next few years she illustrated several more books for OUP, and had two daughters, working from a flat on Fulham Road.

|

| Margery Gill, from The Guardian obituary, by Matthew Weaver |

As her use of line grew bolder, she became more in demand, working for Bodley Head, Puffin and Jonathan Cape, as well as teaching drawing at Maidstone College of Art. Her work suited the kitchen sink realism of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, and she illustrated twenty books in the ‘50s and a staggering sixty six in the ‘60s.

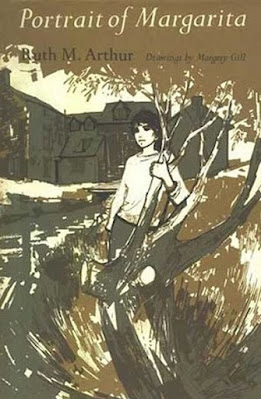

|

| Portrait of Margarita, by Ruth M Arthur illustrated by Margery Gill, Atheneum Books, 1968 |

Most of her colour covers around this time used the Plasticowell lithographic process – two or more colours over a pen and ink drawing. According to book designer, Ness Wood, illustration in the 1960s was ‘all about the drawing'. She says, ‘There are no special effects, it’s about the tone and composition through drama - it makes the reader really look at the images'.

A good example is my favourite of Margery’s illustrations from Over Sea, Under Stone. Barney, the youngest child, has been grabbed during a carnival and taken to a deserted looking house, where the ominous Mr Hastings grills him for information.

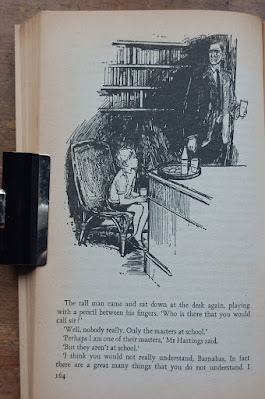

|

| Barney and Mr Hastings, Over Sea, Under Stone, by Susan Cooper, illustrated by Margery Gill, Jonathan Cape, 1965 |

Margery could have chosen to show the boy’s fear and frustration at being captured, or a moment of action, such as him being bundled into a car. Instead she chose this still, tense moment, the two characters locked in each other’s gaze.

The image plays with contrast – tonally, with the light figure of Barney and the darkness surrounding Mr Hastings, but also in the composition – Mr Hastings towers over the seated Barney, who is all elbows and knees. Barney is ill at ease, his hunched position echoing the curves of the chair and the circular tray on the desk. In contrast, Mr Hastings stands stiff and upright, in his formal suit, between the vertical lines of the bookshelf and the bottle on the tray.

Margery Gill has completely captured the essence of the scene, in which Mr Hastings is quietly menacing, and Barney is both bold and frightened by turns.

I wrote to Susan Cooper to ask about Margery, and she told me that although she wasn’t involved in choosing an illustrator for her first children’s book, she thinks she asked for Margery for her next book, Dawn of Fear (1972).

Her drawings were perfect. We must both have been working from similar memories, having both been children in World War II England.

Susan Cooper

|

| Dawn of Fear, by Susan Cooper, illustrated by Margery Gill, Puffin, 1972 |

One of Cooper's prized possessions is an original drawing from Over Sea, Under Stone, which hangs on her study wall. In this illustration we see the three characters’ backs, matching the three standing stones, almost characters themselves. The drama is in the inky darkness and lines of the swirling clouds.

|

| Over Sea, Under Stone by Susan Cooper, illustrated by Margery Gill, Jonathan Cape, 1965 |

Susan discussed illustrators for The Dark is Rising (1973) with her editor, Margaret K. McElderry, who felt that Margery wasn’t right for this book, and commissioned Alan E. Cober. He added an octopus which would have outraged my eleven-year-old self, but fortunately my book’s cover was illustrated by Michael Heslop.

It seems Margery’s work was less in demand by this time – when according to her obituary in the Guardian by Matthew Weaver, cartoony drawings were more popular in children’s books.

In the 1980s she illustrated fewer books and retired after illustrating her last book in 1985. Although she had arthritis in her hands, she continued gardening and doing voluntary work.

Matthew Weaver remembers her as someone who ‘smoked and laughed a lot . . . she was a perfectionist, but never precious or pretentious. She continuously revised her work by scratching out lines with a scalpel'.

When she heard that the 1961 edition of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess was reissued in 2008 with her name on the title page as Margery Hill, she just laughed.

|

| Margery Gill, by Paddy Jordan |

She also said:

Every drawing is a fight which I really enjoy. I enjoy, too, the failures, and starting again.

Initially I found this idea surprising, thinking that drawing from life can be so exciting, playful and relaxing. But then creating finished artwork from what we see in our mind’s eye can be a challenge, so I’m going to experiment with the idea that the ‘fight’ can be enjoyable, and maybe the failures too.

Writing about Margery Gill has reminded me that looking closely at another artist’s life can unlock a world of inspiration, and as I work on my own composition, tone and sense of place, I’m trying to keep in mind the contrast and drama that I admire in her work.

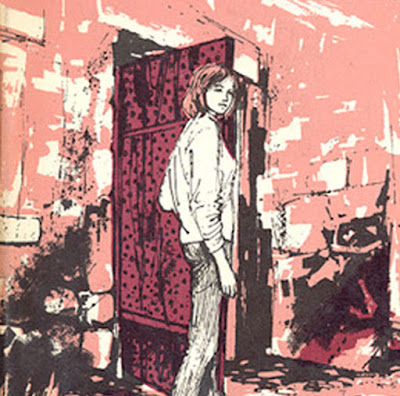

*Header picture, Requiem for a Princess, by Ruth M Arthur,

Atheneum Books 1967, illustration by Margery Gill

******************************************************************

Martha Lightfoot has illustrated several picture books and is currently writing and illustrating her own stories, and working with Aurora Theatre. Find her on Instagram and Twitter

This blog has more information about Margery Gill:

https://bearalley.blogspot.com/2008/12/margery-gill-1925-2008.html

No comments:

We love comments and really appreciate the time it takes to leave one.

Interesting and pithy reactions to a post are brilliant but we also LOVE it when people just say they've read and enjoyed.

We've made it easy to comment by losing the 'are you human?' test, which means we get a lot of spam. Fortunately, Blogger recognises these, so most, if not all, anonymous comments are deleted without reading.