REPRESENTATION New Lunar Year

Happy (belated) New Lunar Year everyone! Eva Wong Nava gives us an insight into how this festival is celebrated across Asian communities and its influence on children's literature.

If you’re wondering why there is a sudden ROAR in the air, it is because the Chinese diaspora all over the world is celebrating the Year of the Tiger! The tiger was the third animal to cross the Heavenly River and hence the Jade Emperor decreed that Tiger would be one of the twelve zodiac animals, henceforth ensuring that humankind had a way to tell time and seasons. In Chinese mythology, the tiger is the symbol of bravery, wisdom, and strength.

The Chinese follow a lunar-solar calendar, and for the Chinese diaspora, the new year began on a new moon on February 1st. But, on Monday night, January 31st, Chinese families world-wide gathered for their annual Reunion Dinner. The Reunion, as it is typically referred to, is an important night. A New Year’s Reunion by Yu Li-Qiong, illustrated by Zhu Cheng-Liang (Walker Books, 2012) explains what this night is. Special dishes are eaten to ring in the new year. Each dish is symbolic and represents the hopes and wishes for the year to come.

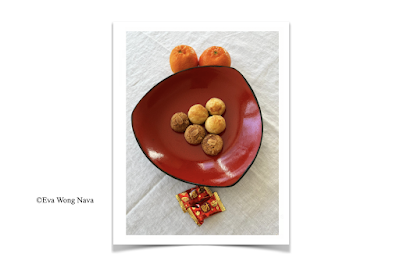

Dumplings, also known as jiăozi ( 饺 子 ) in Mandarin, symbolise family members reuniting; the shape of the dumpling also resembles an ingot, a form of money used in ancient China. Hence, a dish of dumplings symbolises both reunion and prosperity. A mountain of mandarins or júzi ( 桔子 ) is significant for its association to a mountain of gold. In the exchanging of two mandarins, Chinese people are symbolically exchanging good luck and good wishes, and gold.

The Chinese love word-play, as one character or word can have four different sounds, with more than one meaning. For example, a dish of steamed fish or yú ( 魚 ) means abundance because yú ( 魚 ) sounds like y ù ( 裕 ), the latter meaning just that – abundance. And a sticky rice dessert called niángāo ( 年糕 ) is a wish to climb higher and higher to success every year, because nián ( 黏 ), which means sticky, is the homophone for nián ( 年 ) which means year – two words, same sound, two different meanings. G āo ( 高 ) means high, but gāo ( 糕 ) means cake, so the more cake you eat, the higher you will climb. What a fun way to symbolically climb the ladder of success. Like English word puns, which are great for learning the nuances of the English language, Chinese word puns are a fun way to learn Mandarin and a great resource to understand the Chinese culture.

And if you’re like my children, who love the lion dance, then picture books like Joyce Chng’s Dragon Dancer (Lantana Publishing, 2018) will thrill your children with its lyrical storytelling, and the gorgeous illustrations by Jeremy Pailler are eye candies for those who love a good visual story.

For readers aged 6+, Maisie Chan has a series of books called Tiger Warrior (Orchard Books/Hachette). The cover illustrations are by Alan Brown. There are currently three books that will capture your child’s imagination, transporting them into another world.

One festival, many ways to celebrate

It is good to note that while the Chinese and the diaspora are celebrating the Chinese New Year, another country in Southeast Asia, Vietnam, is celebrating Tết Nguyên Đán. The Vietnamese New Year is similar to the Chinese one, but the Vietnamese and its diaspora have their own way to celebrate this festival. Let’s not forget the Koreans who call their new year, Seollal, and who also have their unique way of celebrating this important day. To the Japanese, it is Shogatsu or Oshogatsu that they celebrate with their family and friends. All these different new years fall on the same day each year in the Gregorian calendar. As there are so many variations to this lunar-solar festival, it is no wonder that you may hear this East Asian and Southeast Asian festival being referred to as the lunar new year.

After devouring all these books, it is time to put your voices together and say ROAR! Tiger magic is real, and those who roar the loudest are blessed with good luck!

The editorial team at Words & Pictures would like to wish all our East and Southeast Asian readers and members a GRRRrrreeeaaatttt and RoaRsome Tiger Year!

*Header illustration by ©Natelle Quek

|

| ©Eva Wong Nava |

Eve Wong Nava is a children’s book author who loves tiger tales. She was born on a tropical island where monsoon winds blow and tigers once roamed freely. When the winds changed, she moved to cooler climates for love, work, and family.

Eva combines degrees in English Literature and Art History and she often writes stories inspired by her culture, which is fantastical and magical. As a monkey child, she had a childhood filled with mischief and antics. Her favourite deity is the Monkey King.

Eva has written an award-winning middle-grade novel about a boy on the spectrum and his relationship with Monkey, the god who can transform a needle into a staff. She writes across age groups and her recent book is a YA historical novel, which was long-listed for a prize by the SoA. Eva has forthcoming books that will keep children roaring with excitement. She lives in the Land of Albion with a tiger, dog, and goat. Find Eva at https://www.evawongnava.com and on Twitter and Instagram @evawongnava

Natelle Quek is a Malaysian-born children’s book illustrator who has been drawing for as long as she could hold a pencil. She was awarded the SCBWI BIPOC Women's Scholarship in 2020, and has since gone on to illustrate picture books and middle grade novels. She currently lives in leafy, historic Kent with her husband, a grumpy cat, and a loud-snoring dog. Find Natelle at http://natellequek.com and on Instagram @natelledrawsstuff

Gulfem Wormald is the Editor of Words & Pictures. Contact: editor@britishscbwi.org Twitter: @GulfemWormald

No comments:

We love comments and really appreciate the time it takes to leave one.

Interesting and pithy reactions to a post are brilliant but we also LOVE it when people just say they've read and enjoyed.

We've made it easy to comment by losing the 'are you human?' test, which means we get a lot of spam. Fortunately, Blogger recognises these, so most, if not all, anonymous comments are deleted without reading.