REPRESENTATION East and Southeast Asian naming convention

What’s in a name? Representation Features Editor Eva Wong Nava takes a look at some children’s books about names, and explains the naming convention in East and Southeast Asian cultures.

I was asked recently if I had a Chinese name. I was hesitant in replying. My name at birth was Eva Wong Siew Luan, as per the naming convention for many Chinese people living in the diaspora in Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam and Brunei (just some of the countries I know in Southeast Asia with this convention). Siew is my generation name, so my sisters are Siew Ping and Siew Ling, and like me, they were also given Christian names, and they are Emily and Edna, respectively. Luan is my personal/individual name. But in the Chinese referencing convention everyone is referred to by both their generation and personal name: in my case, Siew Luan.

In Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei, non-Chinese names are known as Christian names, even though they may not be Biblical ones. Edna is definitely not a Biblical name, though it is a Hebrew name, but that’s my youngest sister’s "Christian" name. Not every Chinese person in Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, China, Taiwan, America, Canada and Britain have official Christian names. Many give themselves Christian names as teens or adults. So, for someone who was named Mee Ying at birth, she could become Mary as an adult. But in official documents, she would still be Mee Ying (add family name). There are myriad reasons why some Chinese people have chosen to do this. Finger on my nose tells me that many just want to fit in with how their western counterparts are named.

Chinese names always begin with the family name — and mine was Wong Siew Luan. My full name, which includes my Christian name, was Eva Wong Siew Luan, as mentioned, because Eva is my official name, and it appears in my birth certificate. Today, I am Eva Wong, a naturalised British citizen. I decided to remove Siew Luan when I took British citizenship in 2005. This was because I was tired of having to explain to the authorities that my family name is WONG, not Luan. I have regretted this decision ever since. I feel that in stripping myself of my Chinese name, albeit a self-imposed one, I’d stripped myself of my Chinese heritage.

On the other hand, my friend Mee Ying doesn’t have this problem because in her birth certificate and official documents, she is Mee Ying Louie, with Louie being her surname, as understood in Anglo-European naming conventions — personal name followed by family name. Louie is also the Anglicised spelling of Lui. Her parents were immigrants from Hong Kong, who came to the UK during the 1960s under the auspices of the British government to work in Great Britain. As Mr Louie didn’t speak English very well, the clerk who spelled his surname had decided to spell Lui in this fancy way, making it look somewhat French. But, in reality it was a phonetic spelling of this Cantonese family name.

WONG is the anglicised spelling for 黄, pronounced wong in Cantonese and huang in Mandarin. The Chinese character is the same for yellow, the colour. So, for some people with this surname, they could choose to spell Wong as Huang, if they speak Mandarin. This is what’s known as pinyin names. So, Wong Siew Luan in pinyin would be Huang Xiuluan.

What’s in a Chinese name?

Chinese people take pride in naming their children. They would consult almanacs, fortune tellers and wise relatives before a child is named. Names are aspirational — parents hope that their children will live up to their names. It was my Teochew-speaking maternal grandfather who named me, his first grandchild. Siew means refined and graceful and Luan is the name of a mythical and magical bird in Chinese mythology. In ancient Chinese mythology, a sighting of the luan indicates that there is peace, among other very auspicious signs linked to this divine bird. In naming me this way, my parents hoped that I would fly to great heights of success since the luan is a deified bird, and while doing that, I must remember to be graceful!

Why do Chinese naming conventions begin with the family name first, followed by the individual’s name?

In Chinese culture, the family unit is more important than the individual. This naming convention reflects how Chinese people think and function: the family trumps the individual. When an individual succeeds, they bring honour to their family, and vice versa when they fail, they bring dishonour to the family unit. In ancient China, a person was often referred to as ‘the Wong family’s daughter or son’. So, if I were born then, I would be referred to as ‘the eldest daughter of the Wong family of [insert address].’

The Chinese community isn’t the only community with naming conventions. All cultures have their own naming conventions and traditions. Catholics have a given name, a baptism name, a confirmation name, or they may name their children after important people in the family whose names and memories they want to honour. My Italian husband’s name was taken from his grandfather's and his baptism name was inspired by that of a saint.

Alma and How She Got Her Name by Juana Martinez-Neal is a picture book story of a little girl, Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela, and how she got her six names. Alma learns that all her names are significant and meaningful because she was named after important relatives in her family.

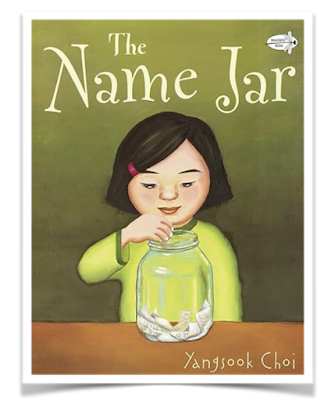

In another picture book, The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi, a Korean-American author-illustrator, Unhei is anxious about fitting in at her new school. What happens if people can’t say her name right? So she chooses an “American” name, but none of these names feels right, and in the end, she learns that the best name is her own name. It’s good to know that the Korean naming convention is similar to the Chinese one, and in this case, the author’s name should be CHOI Yangsook, if she had followed the Korean convention.

This picture book, with gorgeous illustrations by Khao is an exhortation to the world to "say my name". The writing is lyrical, each beginning with My name is..., and it is a celebration of the different ways people are named.

When I had to think of a name for my main character in I Love Chinese New Year, I thought very hard about not giving her an English (or Christian) name. But, I was also mindful of giving her a name that all children can pronounce well, whether they are reading in English or another language. So, I chose Mai-Anne, which means beautiful peace in Mandarin. In French, Mai-Anne would sound the same as in English. The illustrator for the book is Xin Li. She is China-born but lives in Norway. Xin was previously known as Li Xin, but she had decided to follow the European naming convention by tucking her family name at the back. I know why she had done this — it’s just too tiring to always have to explain to people what your name is.

Here’s where you can find more books about naming conventions and about names in children’s books. Many of these books indicate to young readers how our names are linked to our identities and cultures.

If you have a naming convention in your culture, let us know.

*Header image: Ell Rose and Tita Berredo;

all other images courtesy of the authors

*

*

Tita Berredo is the Illustrator Coordinator of SCBWI British Isles and the Art Director of Words & Pictures. Contact illuscoordinator@britishscbwi.org

Incredibly informative. Thank you!

ReplyDelete