EVENTS Writing for Children: Diversity and Inclusion

How do you make children's literature more diverse and inclusive? Elizabeth Frattaroli reports on a SCBWI Scotland event at Edinburgh International Book Festival.

On the 28th of August Elizabeth Frattaroli attended a Scottish SCBWI event at the Edinburgh International Book Festival hosted by one of the current network organisers, Onie Tibbett, and former network organiser and soon to be debut author, Yvonne Banham, whose book, The Dark and Dangerous Gifts of Delores Mackenzie, will be published by Firefly next year.

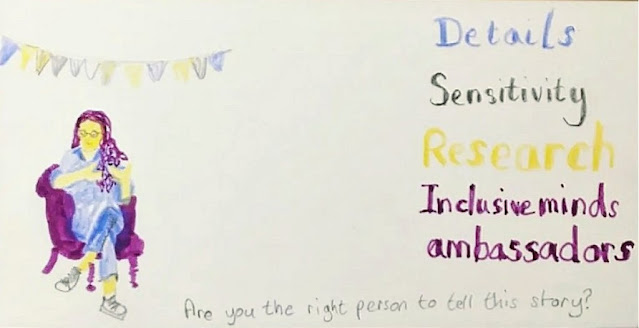

The conversation began with each of the five panel members introducing themselves and describing their physical appearance, with Onie acknowledging that conversations around these issues can be sensitive and emotionally challenging. There is a need to increase diversity and inclusion in our writing and to elevate own voices and stories from marginalised communities, while ensuring sensitivity and that it is not done or seen as a token gesture.

The following is a general summary of the discussion rather than direct quotes from those involved.

Yvonne: So, how do we balance writing experiences that are not our own, with the pressure for all writers to write a cast of inclusive characters?

Az: The key thing as writers is that we all want to do the right thing but that we should approach writing with humility and respect. Ensure that you speak to people from the communities so that you get it right. Ask yourself why you want to write it through those eyes – are you the best person to write from that perspective? Could the character have been any colour or race? When I was writing about Sami, a Syrian refugee, I first of all looked for other stories out there that I could promote. Have a look and see if there are any other writers doing this. I trod carefully and did it slowly, as to do it properly needs time and effort.

Sally: There’s room for writing inclusively on lots of different levels and it’s important that publishers are reading and making space, as they haven’t always done so in the past. It’s also important for authors to represent that diversity as long as it’s appropriate to the book. You need to have a close connection with that community and a strong reason to write the book.

Julie: There’s a difference between the protagonist and the supporting cast. Historically, from a disabled writer’s perspective, disability has often been used as a narrative device or a character quirk. But it's also important that publishers represent diversity in staff hires. We are all cogs in the massive publishing machine and agents, editors and authors all need to increase diversity. We must always think about who the reader is, and who are you to write it.

We’ve seen instances of policing and of authors being forced to reveal parts of their identity that they maybe didn’t want to, and the publishing industry itself isn’t really helping writers navigate this. Solidarity between other members of society is very important.

Onie: The question of ‘is it your story’ is so important, but equally so is the way the story is told. How do writers go about ensuring that the characters they are writing are portrayed sensitively and appropriately?

Sally: It’s all about authenticity. What are you looking for and what questions would you ask an author who has written outwith their lived experience? If the USP of the book is, for example, a refugee story, you will need to publicly stand behind that book. You perhaps have a close connection and/or have maybe worked with refugees. But you must have some reason for writing that particular book.

Also, it’s really common to weave diversity in incidentally through the rich tapestry of a book. Floris supported an author to work with Inclusive Minds where the lead character was disabled, even though the book wasn’t about this. They were set up with an Inclusion Ambassador and a charity, and afterwards an expert also read through it and gave comments and support from the community.

Az: I’m Leicester born and bred, which is one of the most diverse cities in the country, so was able to write Fight Back partly from my own experience of growing up there. However, I also spoke to as many people as possible as I knew my own experiences wouldn’t be representative of everyone’s. The more people who read your work, the better chance there is of making it balanced.

I don’t believe in sensitivity readers as such, and Inclusive Minds discourage the use of the term ‘sensitivity reader’, as one person will read from their own one lived experience. Inclusion Ambassadors meanwhile are part of a huge team and are expert readers, who will read books across a huge range, and so are able to identify and pick out harmful tropes. Also, sensitivity readers will read the book when it is pretty much ready and so it leaves no time to fix it and can feel like it’s simply a box ticking exercise, which is actually pretty offensive. At Inclusive Minds we have been encouraging publishers to approach us at the early stages. Inclusion readers are people who read a book at a developmental stage and are willing to do more work with you.

One of the key things is to ask, does this character have a back story and are they as human as possible? They need to feel real and not 2D. What are their hopes and desires? In movies, the sidekick is often there to support the main character, but we should still explore who this person is and make them rounded, as often again they are a tick box and not respected as human beings in their own right.

Write what you want, but the way you approach it is key. You should always question it. When someone gets cancelled, it usually starts with the little things and then snowballs. For example, if writing about a black person, has hair been mentioned? I was watching a film recently where a Chinese character took their shoes off at the back door. It’s the little things that matter and it's why nuance and research are such a huge thing. You need the right people reading your book to pick up on these nuances.

Julie: You can tell where people haven’t done the work. There is a well-known and very successful children’s book where the main character is facially disfigured and, while I loved it and had empathy for the main character, it has since been questioned as quite ablest in some ways. The protagonist is ‘herded’ by the able supporting cast who tell him that he’s just like them and can do anything, instead of celebrating who he is.

We also still see villains with scars and the sole purpose of a disabled character to validate a non-disabled character, for example Tiny Tim and Scrooge. We need to give them their own full life and character and take their needs into account/move away from damaging tropes.

Working with communities such as Inclusive Minds is important and, while writers might not be able to afford it on their own, the hope is that the publisher would pay.

There is always going to be a bit of controversy and divisiveness, but I’m grateful for representation being in books and welcome it if done sensitively and with consideration. Solidarity of marginalised communities is increasing.

Yvonne: Is playing safe and writing only from your own lived experience more harmful?

Az: With Boy, Everywhere I wanted to change the narrative and also raise money to help Syrians. It felt like it was a responsibility, and it took a lot of effort, but I wanted to write it from a place of love and care as you would do if you were writing an autobiography, for example, and writing about your own family. So, it was quite draining and very exhausting. I thought Fight Back would be easier to write as it was Own Voices, but it wasn’t. I realised that my own voice on its own was not enough, what about all the other Muslims out there? A big fear is getting cancelled. You need to remember you are writing about real people and make sure you haven’t been offensive. Even if you’re writing from your own perspective, you’re still writing about others, so you have to be very careful not to enforce stereotypes and be aware of their experiences.

Some authors have a sense of entitlement, but we don’t have to write everything. If you’re wary and don’t think you can do it justice, let somebody else do it. However, there is space for every story as no one else will be able to write your story in the same way. If you’re coming from the right place, your heart will show on the page.

Onie: What should writers do if they get it wrong? How should they respond?

Julie: First of all ask yourself, if you got it wrong, why did you? Did you not do the research? Where did an agent/editor/publisher get it wrong too? People with power in the system should have picked it up and said something. We’re at a bit of a tipping point in the industry and writers should always ask why they are doing it and is there somebody out there who could do it better. Is the risk too great?

Sally: Where does responsibility lie? It lies with an author doing sufficient research, an agent asking questions about sensitivity, and definitely publishers asking questions at acquisitions. Once contracted, it is the responsibility of an author and editor to write it well and work as a team.

However, if you do get it wrong, don’t react straight away – speak to your agent and editor first as they will have experience in this area and will be able to support you so that you can respond in a calm and measured way.

Az: Sometimes it’s better not to say anything and hope it goes away without escalating, but I think the right thing to do is apologise and say that you have learnt and will go away and do things better. Maybe have a conversation saying this is why I did this, or maybe I shouldn’t have done this. Everyone has internalised bias and biases are everywhere, so the work we need to do is for everybody. You’ve taken the first step today by coming along and being part of a conversation about fair representation.

You can access the Inklusion Guide website here.

The event was also live tweeted @SCBWI_BI by Sarah Broadley under #InclusiveKidLit

Elizabeth Frattaroli is a YA and MG writer who lives by the sea near Dundee. She has been longlisted in The Bath Children’s Novel Award, the Mslexia Children’s Novel Award and the WriteMentor Children's Novel Award and was selected by Creative Scotland for their Our Voices Emerging Writer programme in 2022. She is on Twitter as @ELIZFRAT.

*

No comments:

We love comments and really appreciate the time it takes to leave one.

Interesting and pithy reactions to a post are brilliant but we also LOVE it when people just say they've read and enjoyed.

We've made it easy to comment by losing the 'are you human?' test, which means we get a lot of spam. Fortunately, Blogger recognises these, so most, if not all, anonymous comments are deleted without reading.